"Essayer" Means "To Try"

The Painted Protest • my little art world • Andrea Fraser on wtf we're doing • History and Fear • comedy & writing class updates

A critic, to me, is rarely a cipher for the discipline. It’s usually someone that I kind of know, or have seen around, or whose ascension I have tracked on social media, or whom I loved dearly for a time then and vowed never to see again. I’ve met Dean Kissick only a few times, the first at a dinner at Jeffrey Deitch’s house during Jeffrey’s brief tenure at the MOCA (we were so mad at his appointment, it was quaint. It lasted all of five minutes). I was still trying to dress interesting. #GIRLBOSS had just reached the New York Times bestseller list. Jeffrey introduced me and my companion to its author by saying “Sophia this is Andrew, he’s a brilliant critic and my favorite writer in Los Angeles. Andrew this is Sophia, she’s a fashion entrepreneur and a New York Times best-selling author.” Then, to save time I suppose, he waved a hand at me and addressed them both. “And this is Christina.” Dean and I were seated at a provisional table near the edge of the pool and exchanged longform pleasantries over salad bricolage. I’ve been trying to situate myself in relation to his recent essay in Harper’s. The atmospheric pressure to have a read on it has passed so now I can think.

Because I entered the art world through the side door, I remained for many years unaware what floor I was on (it wasn’t the bottom). There was a hierarchy, imperceptible but felt. My alienation was girlish, hopeful, signaling only social deficiency from within. It bred focus, not cynicism. I felt the art world was a place that could teach me things. I had no peers and no practice of my own. I frequented museums and blue chip or mid-tier galleries from a list given to me by my first editor, long before I developed the confidence to label a gallery ‘mid-tier’ or ‘bluechip’ on my own reconnaissance. That the objects I examined warranted the depth of scrutiny I was tasked to provide seemed like a given. Marcel Duchamp said that artists play chess with history, and I, as a critic, was trying to play Jeopardy with the art. There was an answer there, in the faint dots of corn yellow paint that glowed like a bulb or in the sleek lavender plank that leaned on the wall or in the dirty sagging thing with fragments of poetry stitched on it in red thread. In this pile of candy, we believe there is an answer. I only had to figure out the right question and then rewrite it so it seemed like I had the answer all along.

The second time I met Dean we smoked cigarettes outside of a comedy show in Echo Park that took place in what can only be described as a lesbian homegoods store. It must have been at least ten years ago, as I was still a few months away from attempting stand-up comedy myself. Going to openings was called making the rounds, which felt old-timey and conservative to me, like what Edith Wharton characters do before a ball, but it remains an efficient way of summarizing plans for four or five dinner stops. Are you making the rounds this weekend? Yes. Ok I’ll see you there. I had recently added comedy shows to my rounds, making four or five dinner stops and leaving each one early, unearthing the places where my worlds came together in a slim overlap. I wanted something. I didn’t know what it was, so I kept busy and went anywhere and everywhere to see if I’d recognize it when I saw it. I had a houseguest, my best friend from high school, and she was welcome to my half-attentions in the thirty-minute window between coming home from my 9-5, slamming my purse down, taking a cold shower, dressing anew and then slamming the door on the way out. She’d sit on the couch and look up from a book or a salad as I whizzed by. “Just looking at you makes me tired” she would say.

I did eventually find what I wanted. I have since done stand-up comedy in every damn kind of place you can imagine, up to and including a lesbian homegoods store, and I can guarantee, from experience, that if the audience has an art world contingent there will be clusters of cultural commentators huddled outside the venue, speculating on how much better they probably could be at whatever is going on inside. Yes, comedy clubs are hotbeds of racism and misogyny but they are also places where artists get paid, which is often more than I can say for a mid-tier gallery comedy night (shoutouts to Night Gallery, Nazarian-Curcio, and Baert for ponying up over the years). “I have jokes you know” Dean said to me, but they were all related to fashion designers and animal puns, so no one would get them. I said I would get them and so he did them for me out on the street. The set up for one was something about a UK designer who has dark cirlces around his eyes and loves to eat bamboo.

“It’s JW PAND-erson!!!” he said after a pause.

I’m surprised at the force with which naysayers attack his snobbery, the pimping out of his mother’s legs as an anecdotal opener (the best part IMO), and worst of all his nostalgia for a previous time. It’s vitriol masquerading as offense. I think it’s OK to be nostalgic for the 2010’s. They were pretty fucking awesome. I swept across the globe on tides of money and drugs and mean girls with clipboards, phenomena that were natural to me as warm ocean currents. I carried an old-timey and conservative sense of journalism ethics, which made a great cover for my social anxiety. I didn’t make friends or sleep with artists. I rode the tide in a bubble meant to keep the art world at bay, to prevent any one person in it from sharpening into particularity and making me feel some sort of way. I reserved my emotions for the work, which has proven, at times, to be both an asset and a liability. It was years of making the rounds before I ever told a gallerist about my personal life or let a curator put his tongue in me. The latter proved to be a mistake, but it did show me that the risk of being a full human in the culture industry is one I am willing to take. Sometimes. That same curator told me over breakfast at our Venice Biennale AirBNB, “I like that you write your feelings. It’s important. I mean, Hal Foster writes about fear, and it’s like, okay… but what is Hal Foster afraid of?”

I read many responses to The Essay. The jeering, the exaggerated sighs of finally and the pissy moralistic ripostes of how dare you. It’s not clear what we’re all afraid of, but clearly we are afraid. I agree, politics ruined contemporary art. Not because identity politics became a curatorial mode, but because politics writ large have made us afraid.

Almost as palate cleanser, Harper’s most recent cover story is an apolitical personal essay about going to Bonaroo while sober, but they did publish several letters written to Harper’s in response to The Essay, as well as Dean’s response to one of the responses. I tell my writing students to pay attention to the heat that rises up in them around their subject matter. It means they are on the right track in wanting to figure something out. My therapist says I should write fiction, since I’m so obsessed with people. I am obsessed with people, but I am also a historical materialist, and the ongoing “crisis” of criticism has much to do with an open secret Dean shares in a reader response letter tucked into the very pack of the issue, “that most contemporary art is boring and mediocre.” We all know this. Gilda Williams writes in her book How to Write About Contemporary Art that the worst thing a critic can do is become trigger happy with their own intellect. “Sometimes it’s just picture of the artist’s dog.” A critic is responsible for commenting on much more than the slim sliver of work that actually warrants the depth of scrutiny we’re tasked to provide. I’m boring myself just talking about it. The art wasn’t better in the 2010s, but the art world was more fun. My former ArtForum editor David Velasco wrote a letter calling Dean’s essay '“an orgy of grievances” and even he had to admit, “I do agree with him on one point: the art world is boring right now.” There is an unspoken but intrinsic nature to the art world that feels obvious to me as an inside-outsider: that it draws from both academia and subculture, that it needs wildcards and autodidacts as much as it needs suits and specialists. That this cocktail of class tension requires an essentially stable social fabric in order to keep its lighthearted fizz should be a given, but it’s hard to keep up when everyone is worried about losing their job.

I am sometimes asked by mainstream outlets what it's like to be “in” the art world, and I always respond that the art world isn’t a place. It’s a group of sixty to eighty people—who, as a group, exist only in your mind—that you’ve decided need to take you seriously.

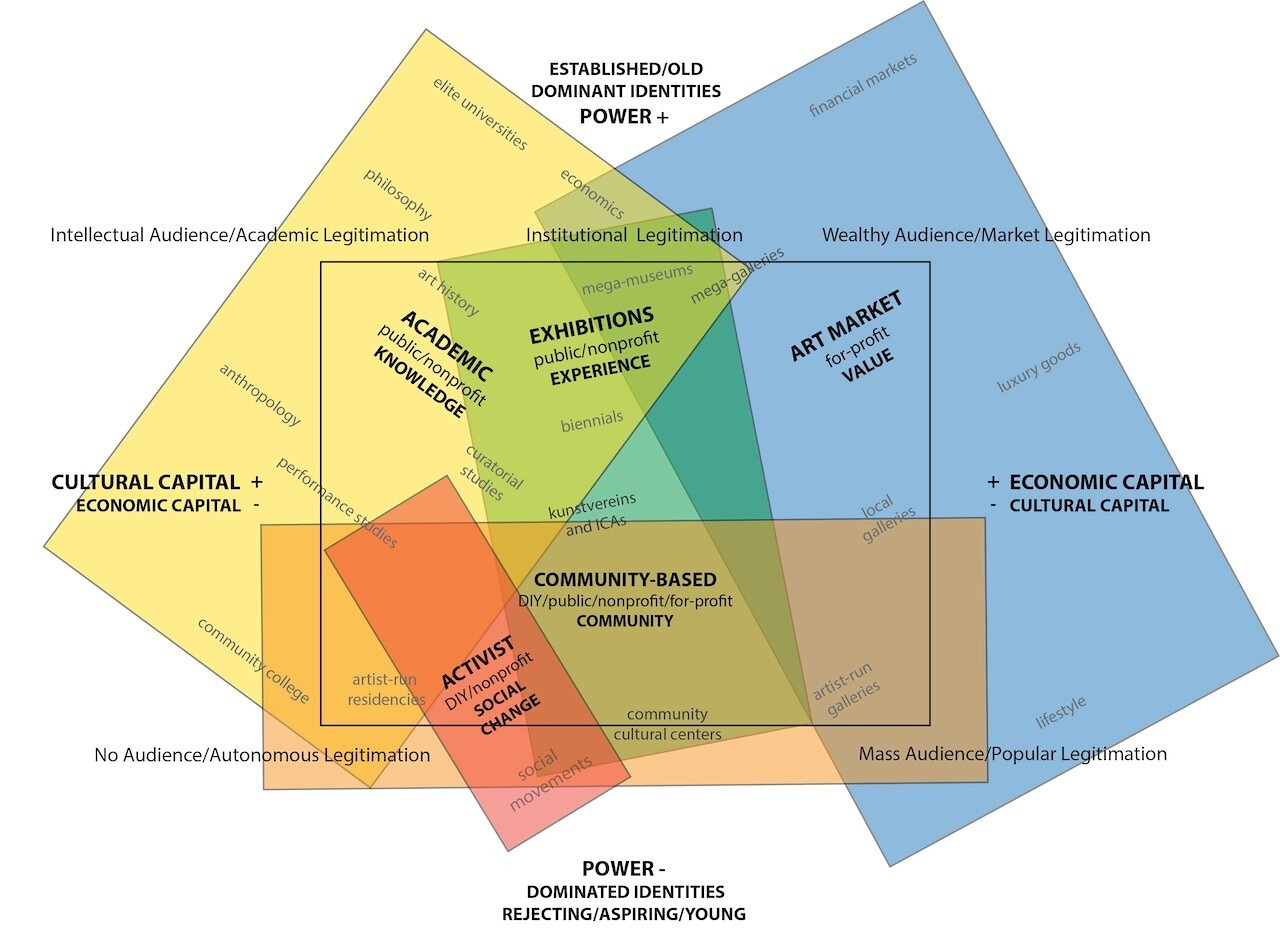

Reflections about the Art World rarely take into account which one they’re talking about. I read a lot of essays last year—on the banana, on the market, on the crisis of criticism, on the place of politics in this, our niche area of cultural concern, suddenly saddled with uncomfortable questions about where the money is coming from and how we’re going to get by. The only text that’s made sense of things to me recently is Andrea Fraser’s e-flux essay “The Field of Contemporary Art: A Diagram”, published in October 2024 to surprisingly little fanfare. Fraser is my favorite artist-writer. Her bone-dry academic style greatly soothes me. It’s lucid. Practical. At first I thought the accompanying diagram was a joke, but no. It earnestly illustrates her argument that there are at least five overlapping art worlds, each producing its own types of capital, each with its own sets of values and codes. Talking across them, as if we all live in one big happy art world, is not the clearest path forward for critiquing what is, for many, a big unhappy art world. I don’t know if these art worlds can ever really correct their own histories, or fully be places for restitution. The attempt doesn’t necessarily alter the ratio of mediocrity, it just makes some people feel guilty and some people feel defensive. I do know that my curiosity about this has superseded my desire to be first in line for salmon steak at the gallery dinner, so I find it difficult to write about what is wrong with the art world because I don’t believe anything has been destroyed. I also remember the first time I was offered an assignment because the original (white) author didn’t think she “should” profile a Mexican artist. I was fine with it because I knew I could do a better job anyway. “Anyone who wants to escape the boundaries of the art field,” Fraser writes, “need look no further than their own desire to function within it.” I have occupied enough varied circles to know that some people really are drinking the kool-aid, believing that art institutions can spoon a glob of justice into the bowls of the marginalized. Some just want to maneuver whatever tide keeps them in travertine bathrooms, bent over the powdered ends of keys.

The thing about art history is that it exists all at once. The best artists, regardless of technique or medium, seem to carry the weight of this, and they don’t even have to be contemporary in order to do it. It’s more disorderly than any diagram can capture, and I have wondered if there is something beyond linear or even dialectical thinking about it, beyond thinking itself. Gavin Matts has a great joke where he says “Have you read history? History is the worst thing that can happen!”

This post is an extended riff on an essay that was killed by an art magazine at the end of last year. They wanted me to do some image-driven Best-Of type bullshit and had trouble with what I picked, a little statue I saw at Museo Anahuacalli when I took my boyfriend to Mexico City for his birthday. I knew I was violating the tacit contract of the assignment, which was not to be honest about the fullness of what actually mattered to me, but to narrow my field of experience to something hot, new, legible. Whatever. Here we are. I’ve thought about Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo a lot recently, how their politics have been reduced to a fun, fiery little feature of their art. Even a nuclear enthusiast can appreciate a Rivera calla lily. I like Anahuacalli. It’s a museum, but also a personal collection, one man’s vision of significance and the use of his power to assert it through his own taste. The darkened stone rooms house rows of objects dating back to the welter of history stamped as “pre-Columbian.” I stopped short in front of this little statue, alarmed by his energy. His armor looks Constructivist, or Dada, movements he predates by 2000 years. He looks ready to bust through the glass and defend himself, which makes me defensive. I’m on the right side of history! I’m innocent! How dare you be afraid of me! Nothing about him signals a conflict between indigenous and now. It’s all happening at once. The fear in his eyes is as modern as losing a job, and just as familiar. We think of good contemporary art as something that has the right sort of glance into the past. Meanwhile the past is looking forward at us, and most likely terrified.

***Chultural Chriticism With Christina starts next Sunday February 9th. We have one or two spots left! I fucking love teaching this class—if you have an inkling of desire toward complicating your own thinking you should totally fucking join us.

***2/5 (tomorrow) Better Half Comedy, Thursday 2/6 Peacock Comedy 2/15 HOT TUB Anniversary Show at The Lodge Room. This one is sold out but there will be standby tix at the door. 2/20 Talkies Comedy and 2/26 Microdose

Talk soon, luh yoo <3

"We think of good contemporary art as something that has the right sort of glance into the past. Meanwhile the past is looking forward at us, and most likely terrified." - so good